What Can We Say Today? Questions for the Revision of the Book of Discipline

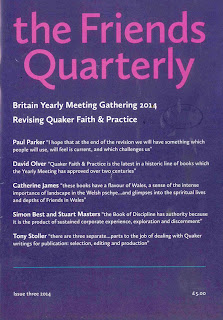

This essay by Simon

Best and Stuart Masters was first published in The Friends Quarterly, Issue Three, 2014.

Introduction

In

her entry on Quaker Discipline (Faith and Practice) in the Historical Dictionary of the Friends (Quakers) Jan Hoffman notes

that ‘when a yearly meeting becomes aware of “spiritual and social inharmonies”

with its Faith and Practice, a

revision will be undertaken to reflect new revelations given” [1]

In Britain, Meeting for Sufferings has recently decided to recommend to Yearly

Meeting that a revision process is initiated (minute S14/02/06) and so it seems

likely that we will soon be entering a period of consultation and discernment

leading to the revision of our Book of Discipline. Now such a process is about far

more than simply changing a few paragraphs and adding one or two new pieces of Quaker

writing. Quaker Faith and Practice seeks

to communicate something vital about who we are, what we do and what we have to

say to the world. It requires each of us to forego a little of our individual

freedom and autonomy in exchange for the opportunity to participate in a

community with a common identity that represents something more than simply the

sum of its parts. It also requires us to accept that, since we are but one part

of a diverse global family of Friends, we cannot possibly produce a definitive

statement of the Quaker way. Instead we seek to make our particular

contribution to a living and evolving faith and practice. The Book of

Discipline has authority because it is the product of sustained corporate

experience, exploration and discernment. In this essay we will attempt to

identify a number of the key issues and questions that will need to be

addressed during the revision process as they relate to the identity, practice

and message of British Friends at this time. We recognise that there may not be

one single answer to these questions but we believe that some answers will be more

acceptable to us as a community than others. One of the great strengths of the

Book of Discipline is that it is has the capacity to reflect both issues on

which we are in unity and those on which a diversity of opinions exists. In

recognising this fact, we would like to emphasise the value of working within two

key areas of creative tension which seem to be characteristic of the Quaker way.

These are:

1. Rooted and Evolving – between our roots in Christianity and the

Quaker heritage and the growing pluralism and questioning of this tradition and

heritage within our communities?

2. Corporate and Individual – between being ‘a gathered people’ with a

common identity, practice and message and the value of individuals who bring a

diversity of gifts and insights to that community?

It

would seem that for some time now the development of British Quakerism has been

weighted quite strongly towards the evolving and individualistic impulse over

that of a rooted and corporate focus. As this reflects dominant cultural

patterns in the wider society, it will be interesting to see whether we are

entering a period in which this trajectory is accelerated or rebalanced.

We

have divided our analysis into five main themes: the question of God & religious

language, the purpose and experience of Quaker worship, the nature and shape of

Quaker testimony, the practice of Quaker discernment and decision making and

the issue of belonging and Quaker community.

‘God’ and Religious

Language

The

Quaker way has always given priority to spiritual experience over the

development of systematic religious thought. That said, it is clear that individuals

and groups need to be able to interpret their experiences and explain their meaning

to others. Language provides us with an essential tool for expression but it is

an imperfect medium. The meanings of words are culturally and contextually

dependent. Therefore, when we express ourselves in words the intended meaning

is not always clear and misunderstandings are always possible. This can be a

particular problem when it comes to expressing religious experience and belief,

since it is here that we struggle to describe something that is ultimately beyond

words. Concerns about being misunderstood or of giving offense can prevent individuals

and groups from sharing the stories of their spiritual journeys and expressing

what they have found to be true. For example, what the theist seeks to affirm may not be the same as what the nontheist feels

the need to deny. Questions to consider:

1.

Should we spend time arguing about what we mean by

the word ‘God’ and the status of ‘God’ (e.g. as an objective reality or as merely

a human concept) or should we give priority instead to the traditional Quaker

practice of attending to the guidance of our inward teaching (however this

might be understood) and seeking to demonstrate the nature of this teacher by

the way in which

our lives are transformed?

2.

Do

we wish to continue to define ourselves as being ‘rooted in Christianity but

open to new light’? Some express doubts about this but given the significance

of our Christian Quaker heritage and the influence of the life and teachings of

Jesus for our practice and the general shape of our testimony, is it possible

to ignore or deny these roots and maintain our integrity?

3.

Should we remove what some believe to be archaic

terminology from our Book of Discipline or would it be better to add to and

expand the range of religious language used to reflect the richness and diversity

of belief that exists within our communities? We know that early Friends used a

large number of different words for the divine presence. Should we continue

this tradition?

4.

Given that the meaning of words change over time, does

the revision process provide us with the opportunity to re-appropriate and

reinterpret traditional religious language in a way that is compatible with our

current insights?

5.

As

a community, should we set any limits to acceptable Quaker belief? Although we

give priority to right living (orthopraxy) over right belief (orthodoxy), our

beliefs can shape our conduct and the very idea that belief is unimportant is

itself a belief. How should we handle this issue?

6.

Do we recognise the danger of becoming too

preoccupied with rationality and factual certainly? Friends have traditionally acknowledged

the limitations of human knowledge and understanding and hence the need for

humility. Are we able to maintain a respect for the value of doubt and mystery

in our lives and in our spiritual journeys?

Worship

The

Quaker way is based on the awareness of a living Spirit that has the power to

teach and transform us. As a result, the practice of Quaker worship is focused

on enabling both individuals and the gathered community to be led to their

inward teacher. Although Quaker worship is primarily a corporate activity,

individual spiritual practice has traditionally been regarded as a crucial discipline

that helps to deepen the worship experience of the whole community. The person

who comes to worship with heart and mind prepared is able to quickly settle

into the collective stillness and contribute to the community’s capacity to

hear and follow the promptings of love and truth. Over the years our understanding

of worship and how it is practiced has diversified reflecting a growing

individualism and pluralism within Quaker communities. In addition, there has

been a significant change in the length of worship. In the seventeenth century it

was often ‘untimed’ and could last for many hours. Pink Dandelion has noted

that the duration of corporate worship has reduced by about half an hour in

each century since.[2] Questions

to consider:

1.

Is

the traditional understanding of Quaker worship as essentially a shared

communal experience beginning to wane? Do we need to reassert the corporate

nature of Quaker worship practice or is this not a problem?

2.

Is

the idea that we aspire to being in a state of unceasing worship at all times

and in all places still meaningful to us? If so, how do we encourage and nurture

such a practice?

3. We know that in our communities there is a diversity of views about what

it is that we are attending to in worship and a variety of different practices

being adopted. Does this weaken the worship experience? Does this matter?

4.

The

issue of leadership and authority can be a controversial one. Do we fully

recognise and value the role and authority of elders in nurturing the spiritual

life of meetings and in ensuring the right ordering of worship? If so, are we

prepared to recognise their authority in undertaking this role?

5.

Is

the centrality of worship as the essential context in which we make decisions

and do our business as a community still something that we are prepared to take

seriously as a spiritual discipline? How can we make this a more vital and

fulfilling aspect of our corporate life?

6.

Do

we wish to emphasise the essential value of worship at all levels of the Society

(at local, area and yearly meeting levels)? If so, how can we encourage greater

participation of Friends at all these levels?

7.

In

order to deepen our experience and reconnect with earlier Quaker practice should

we give a higher priority to encouraging communities to experiment with longer

and untimed worship? How can this be achieved when Friends have increasingly

busy lives?

8. Do we need to be more willing to experiment with a variety of worship forms

to meet the diverse needs of people (e.g. families with young children) and the

demands of a variety of circumstances? If we do, how can we ensure these are in

harmony with traditional Quaker insights?

Testimony

How we live our faith is central to

being a Quaker, ours is a lived faith. Many people first encounter Quakers, or

are drawn to our meetings because of our witness in the world. We have all seen

the acronym of ‘STEPS’ on a badge or leaflet

– this can be a useful hook but by expressing testimony as a list there

is a danger that it becomes just that, a list of values we try to tick off

rather than an expression of our encounter with the divine. As Maud Grainger says:

“Testimony is about the way in which we live

our lives, it is the expression of our faith. Any list of ‘testimonies’ weakens

the idea of witness and action as our lives transformed through worship.”

Having a list also divides them and

allows us to take action in relation to ‘peace’ or ‘sustainability’ without

seeing the connections between these two expressions of testimony. Maud Grainger speaks of testimony in terms of

threads, running through Quaker history:

“If instead we think

of these words – peace, truth, integrity, simplicity, sustainability, equality

as interweaving threads illustrating our witness through history. These threads

touch our lives and at different times we may feel drawn towards one of them,

some of them, or all of them.”

Our testimony arises out of

concerns, which are to be distinguished from things we are concerned about it.

Quaker concern is more than just issues that we are worried about and more than

just good ideas about how we can respond to these issues. Question to consider:

1.

Do those drawn to our meetings by

our social witness understand that what we do in the world is a consequence of

our spiritual experience as individuals and as a community? How can we enable them to see our action in

the world as having a spiritual dimension?

2.

How can we avoid reducing the

complexity of Quaker testimony to four or five words without being overwhelmed

by a sense of helplessness?

3.

How can we enable each other to see

that ‘small steps’ and ‘big actions’ are both equal and equally valid expressions

of testimony and will be right for different people depending on what resonates

with their life and experience?

4.

Are there any expressions of

testimony that we would want to see as fundamental?

Discernment and Decision-Making

The

Quaker way of decision making is unique. It is not easily described in secular

terms and is qualitative different from a process of consensus. In making

decisions as individuals and as a community we must be open to being led, which

may include being led into surprising or difficult places. Recent articles and letters in the Friend

have portrayed issues which have come to various bodies as ‘debates’ between

two (or more) positions. Such language,

while understandable given the language of the world we live in, leads to

division and to questioning of the decision that was reached. The Quaker

process is such that when misunderstood there can be an expectation that everyone

will have their say and be happy with the outcome. The current Book of Disciple

still speaks of our decision making being about seeking the will of God.

However, only 20% of adult Quakers say that they are seeking the will of God in

Meeting for Worship[3],

Clerks do not see their role as helping the meeting to discern the will of God.

Question to consider:

1.

Do we still understand ‘God’ as a

concept that is capable of having a will? If not what words can we use to

describe our experience of making personal and corporate decisions?

2.

Is the Quaker business method still

a practice of discerning leadings or have we moved to a place where consensus

decision making and possibly even majority voting may be better?

3.

Is the traditional understanding

that discernment and decision making occurs in the spirit of worship still

appropriate for us today?

4.

Do all Friends understand the

discipline of upholding decisions reached by Friends when we are not present,

how can we enable this to be a reality?

5.

Do we need to alter our decision

making processes to ensure that all Friends feel a sense of ownership of the

decision? Can we do this and not lose the essence of Quaker discernment?

Belonging and community

Quakerism

is communitarian by its nature. It always has been. We exist in relationship to

each other and the quality of our relationships affects our communal worship,

our decision making and our lives together. Significantly the Quaker community

is different from and greater than the sum of its parts. We can derive great

support and nurture from belonging to a Quaker community. However, being part

of that community carries with it a willingness to be challenged, to be held

accountable, to support others and to contribute to the community. Being part

of a Quaker meeting can feel like very hard work; there are jobs to be done,

roles to be filled, care to be given. It takes a lot just to meet the

requirements of the ‘Church Government’ sections of the Book of Disciple, and

to keep the show on the road. Within the

Religious Society of Friends membership is falling[4],

the proportion of attenders is rising and

fewer attenders are joining and heard the argument that fewer members and more

attenders in a meeting leads to fewer applications for membership. Most of us

will have seen the reality in our meetings of the committed Quakers not in

membership who give considerable time, money and service to the meeting. Questions

to consider:

1.

What does it mean to belong to the

Quaker community, and to a specific meeting or group?

2.

Are we a support group for

individuals each engaged on their own personal and private spiritual journey or

are we a faith community with a corporate life?

3.

How can we ensure that we meet the

duties laid upon us by Yearly Meeting decisions, legal requirements and good

practice without overwhelming meetings and Friends?

4.

Given the reality of falling

membership and deeply committed attenders should we bother having membership?

Is it a purely administrative function and something we can do away with as we

move into the twenty-first century when Quaker communities might become more

fluid, meeting and worshipping in different groupings and in different ways?

5.

In

Listening Spiritually Patricia Loring

writes that ‘the consequence of having no standard [for membership] is that the

meeting conforms to the vision of those it has admitted’.[5] Where do we draw the line in relation to

membership? What are our standards for admitting people to membership? If the

only apparent standard is that they want to join is that sufficient?

6.

In

what ways is saying you belong to a Quaker meeting, or you’re a member of the

Religious Society of Friends similar to or different from saying “I belong to

Greenpeace” or “I’m a member of the National Trust”?

Conclusion

The

letters page of The Friend has already seen people asking for their particular

preferences to be acknowledged in a revised Book of Discipline. That is an

understandable response and there is an extent to which each revision must

respond to these calls. However as we said earlier the process of revision

requires us to sacrifice

some of our individual ego, needs and wants in order to be part of an inclusive

Quaker community. When

potentially divisive situations arise I’m reminded of the following story from

Quaker faith & practice, about the drafting of the epistle for the 1985

World Gathering of Young Friends:

The discussion [had] changed from persons

wanting to ensure that their concerns were heard to wanting to ensure that the

concerns of others were heard and that their needs were met. We had indeed

experienced the transforming power of God’s love. Paul Anderson Quaker faith & practice 2.92

When

it comes to revising the Book of Disciple we will be able to do the same? If we

can then then this may be an enlivening and enriching process for us as a

Yearly Meeting. If we can’t I wonder whether we will we find a volume that we

can even agree on. It is also the case that any revision will result in Friends

resigning their membership. Just as we have our personal faith journeys the

Religious Society of Friends also has a corporate journey. There will be times

when those coincide and others when the corporate journey means that

individuals feel sufficiently out of step that they stand aside and go their

separate ways. While this may be sad we should not be scared of this happening

but accept it.

In

this article we have identified lots of questions that we feel need to be

explored and addressed in the revision process. To a certain extent it doesn’t

matter whether we do this as part of the revision process or as part of a

preparatory process before getting to the substance of what, for example,

chapter 12 might actually say. Of course our answers may very well be varied

and partial and provisional – for that is what the Book of Discipline is – it

is not a definitive text for all time and Friends in the future will want and

need to revise whatever text we approve. However what we can’t do is avoid or

fudge exploration of these various questions.

The

Book of Discipline sets our boundaries, it establishes where the balance

currently is in the tension between rooted and evolving and between corporate

and individual. What it is not is optional. We can’t say “I don’t like it, I’m

not going to use it”. Of course we will find parts of it that express things

closer to the way we would but the parts that challenge us also lead to growth.

It can be an uncomfortable book but that’s one of its strengths because it is

an expression of an uncomfortable faith.

[1]

Abbott, M et al

(2011) Historical Dictionary of the Friends (Quakers), Scarecrow Press, p.99

[2]

Dandelion, Pink (2008) Quakerism: A Very

Short Introduction (Oxford University Press), p.39 & p.48.

[3] National Quaker Survey 2013, www.woodbrooke.org.uk/data/files/CPQS/Initial_findings_Quaker_Survey_2013_PDF.pdf

[4] Membership within Britain Yearly

Meeting has declined on average by 167 people per year over the past ten years

www.quaker.org.uk/sites/default/files/Tabular-statement-2013-web.pdf page 11.

[5]

Patricia

Loring, Listening Spiritually Vol. 2

Corporate Spiritual Practice Among Friends. Philadelipha: Openings Press

and Quaker Press of FGC 1999: 43-44

Comments

Post a Comment